Officials had already expressed concerns about the rise of private equity investment in skilled nursing facilities, citing a lack of transparency and concerns over quality.

Then the coronavirus crisis hit.

As nursing home operators struggle to fight back a disease described as “almost a perfect killing machine for the elderly,” several resident advocates raised worries about the strategies that private equity firms employ upon taking over facilities — and recently released research appears to back up some of their arguments.

A study from researchers at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School, NYU-Stern, and the University of Chicago found that a variety of metrics — from the number of staff hours to overall five-star quality ratings — decline in the immediate wake of a private equity takeover.

“Following buyouts, we observe higher patient volume on the extensive and intensive margins, leading to an increase in bed utilization,” the team concluded. “We also find a robust decline in nursing staff, leading to greater decline in per-patient nursing staff availability. “

That staffing drop in particular raised alarm among resident advocates, particularly as the COVID-19 pandemic continues to spread.

“All it takes is one staff member ignoring standard precautions to expose everybody in a nursing home to dangerous infections,” Michael Connors of California Advocates for Nursing Home Reform told MarketWatch, which this week published an in-depth dive on PE’s growing influence on the nursing home space.

Private equity firms own about 11% of nursing facilities nationwide, according to the study. Investment in the space has accelerated in recent years, with MarketWatch noting that PE firms have poured $5.3 billion into nursing home deals since 2015 — compared to $1 billion between 2010 and 2014.

There are a variety of factors for those trends. Over the last few years, publicly traded real estate investment trusts (REITs) have increasingly worked to shed non-core SNF assets to decrease their exposure to government-reimbursed businesses. In addition, there’s simply a huge volume of PE cash available: At the start of the year, data firm Prequin determined that private equity investors were sitting on $1.5 trillion and ready to invest it in the right deals.

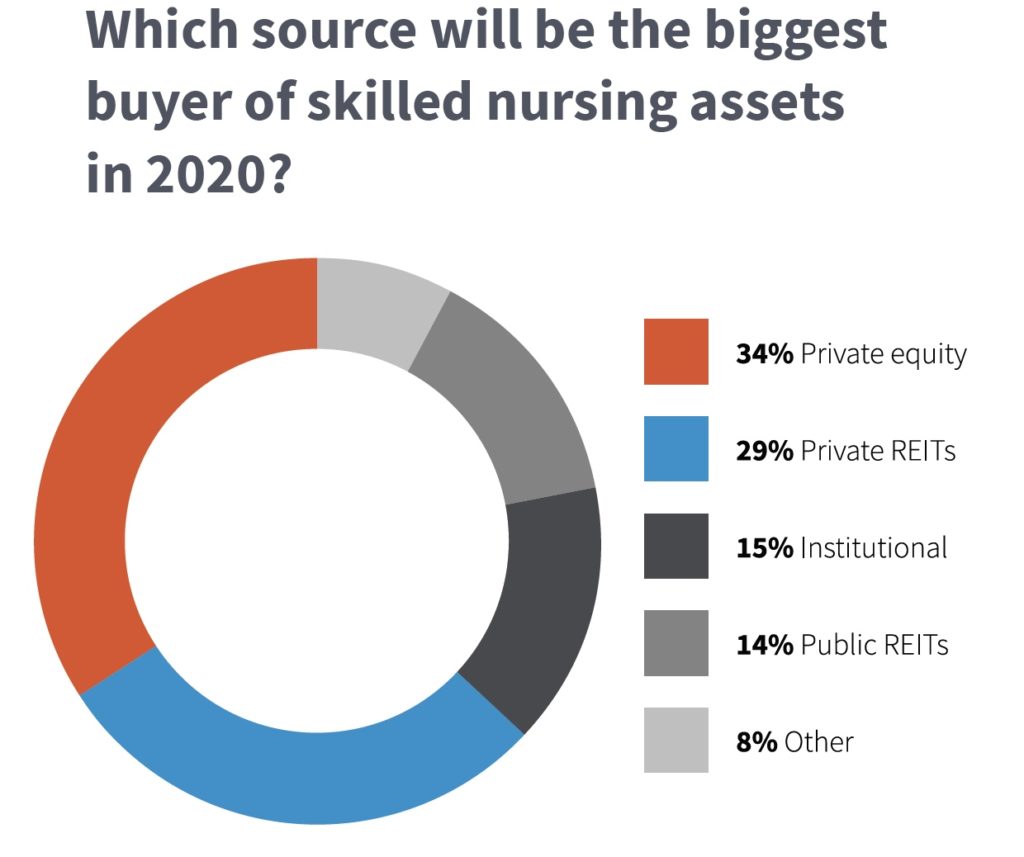

SNN readers also predicted that private equity investors would reign supreme in 2020 in our annual outlook survey, with private REITs in second place — and public REITs lagging far behind.

PE advocates and their operational partners have argued that the model brings a level of flexibility that a public REIT or other larger corporate structure can’t match.

“If you look at the private equity structure, there are clinicians involved at the ownership level. They are experts in the field. They wanted to invest in something they knew about,” Michael Smith, president of Marquis Health Services, told SNN in December 2018.

Marquis serves as the operational subsidiary of the Brick, N.J.-based private investment firm Tryko Partners, and Smith touted the two companies’ ability to adapt to change quickly — implementing new programs and investing in new equipment in a matter of weeks, as opposed to months or years.

“We have so much more freedom and access to real-time improvement,” Smith said at the time.

That’s a particular strength in a skilled nursing landscape transformed by the Patient-Driven Payment Model (PDPM), which required providers to change their operational strategies amid a generational Medicare reimbursement shift. Other macro-level transformations, such as the rise of Medicare Advantage plans and other new payment models, have put an increased premium on being nimble.

But the Wharton-NYU-UChicago study did reveal some broad-based negative trends associated with the years immediately following a building’s purchase by a private equity firm. For example, the researchers tracked declines in overall star ratings and use of frontline caregivers such as licensed practical nurses (LPNs) and certified nurse assistants (CNAs) in the wake of a PE takeover.

While the use of higher-paid registered nurses (RNs) increased, the researchers noted that the buildings tended to see declines in the staffing domains of their five-star ratings, negating the benefits of more RN hours.

“Hence, PE-backed managers may have looked for ways to cut overall salary costs while changing the mix of nursing staff capability to maintain quality and patient experience,” the team noted. “Note, however, that [the study] showed large declines in the quality of RNs after a buyout.”

The study — and the national attention on PE investment in nursing homes — comes at a particularly vulnerable time for providers, which have been forced to adopt a variety of new restrictions and protocols in the fight against COVID-19.

Even before the coronavirus crisis, members of Congress had issued loud public warnings to PE owners of nursing homes.

Back in November, a group of Democratic lawmakers that included former presidential candidate Sen. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts wrote a letter to private equity firms with holdings in the industry — The Carlyle Group, Formation Capital, Fillmore Capital Partners, and Warburg Pincus LLC — asking for more clarity around their operations.

“We are particularly concerned about your firm’s investment in large for-profit nursing home chains, which research has shown often provide worse care than not-for-profit facilities,” the lawmakers wrote in their letters. “In light of these concerns, we request information about your firm, the portfolio companies in which it has invested, and the performance of those investments.”