Beatitudes, a life plan community in Phoenix, Arizona, has become well known for how it provides dementia care, with articles appearing in The New York Times and other publications. That comfort-first approach is spreading throughout the country, with providers seeing better resident outcomes and operational performance in the model.

Three not-for-profit New York City communities—Cobble Hill Health Center, Isabella Geriatric Center and The New Jewish Home in Manhattan—are among those that have adopted the Beatitudes model. They have achieved an array of positive results since doing so, according to Ann Wyatt, manager of palliative and residential care for CaringKind, formerly the New York chapter of the Alzheimer’s Association.

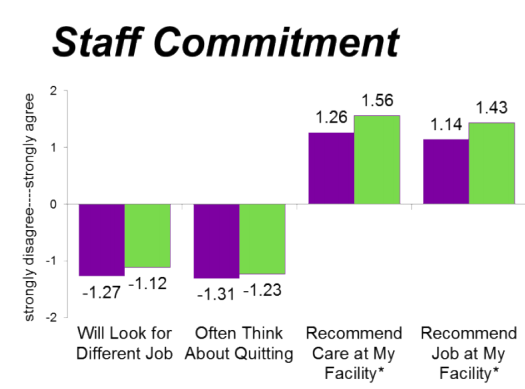

Those results include reduced use of antipsychotic medications, decreased hospitalizations, fewer staff call-outs and increased satisfaction and engagement among residents, staff and families, Wyatt said this week at the American Health Care Association (AHCA) annual conference in Las Vegas.

"What a Palliative Approach to Dementia Care Can Do For Your Community" Presentation

"What a Palliative Approach to Dementia Care Can Do For Your Community" PresentationThe process of transitioning to the Beatitudes model was not simple or fast, however.

Six years ago, CaringKind helped bring the Beatitudes model to the three large NYC facilities, which range between 350 and 700 beds. A 30-month project with ComfortMatters, a consultancy founded by Beatitudes, ended up stretching over five years. That’s in part because shifting to palliative-based dementia care requires overhauling processes as well as educating and training a variety of stakeholders in the new approach.

While the Beatitudes model can’t be boiled down to just a few tips or tricks, these are some of its hallmarks, as explained at AHCA by Wyatt and Tena Alonzo, director of education and research at Beatitudes Campus:

Palliative care is not just end of life care. Providing comfort should be a key objective of caregivers at all times, not just during the last stages of someone’s life, said Alonzo. For people with dementia, comfort includes freedom from pain, the ability to sleep when tired, to eat what they enjoy when they’re hungry and the ability to engage in events and hobbies that make sense to them.

Eliminate the word “behavior.” Caregivers should not see behaviors as something irrational to control, but rather as the resident’s efforts to communicate discomfort. For example, one man would become belligerent around bedtime, until the caregivers learned that throughout his life, he had gone to bed around 4 a.m. and slept until about noon. Once they allowed him to return to this sleep schedule, his behavior totally changed and he was able to go off antipsychotics, Wyatt said.

Create care plans focused on comfort. In a comfort-based approach, care planning needs to delve into the personal history and preferences of each resident, so that staff have some idea of what a comfortable lifestyle might look like for each individual. Throughout the course of care, they will learn more about what brings comfort to each resident, and they should update the care plan accordingly. This might mean including anything from naps after lunch to listening to Frank Sinatra music.

Adopt an appropriate way of identifying and treating pain. People with dementia often cannot grasp or clearly communicate that they are in physical pain, so approaches that rely on residents to self-identify their pain levels or even request their own medications will not work. Rather, facilities should use a framework such as Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia (PAINAD) to identify residents in pain, and they should administer medications or other treatments as appropriate. “Tylenol did the trick in most cases, but it had to be regularly scheduled,” Wyatt said.

With these principles in mind, facilities also need to put the residents first and allow them to do what brings them comfort, even if does not fit a schedule or a typical operational model. Doing so might raise fears about inefficiency, but being resident-focused actually saves time and potentially drives down costs in the long-run, Wyatt and Alonzo said.

"What a Palliative Approach to Dementia Care Can Do For Your Community" Presentation

"What a Palliative Approach to Dementia Care Can Do For Your Community" Presentation

This is because staff spend much less time having to address situations of aggression and agitation, then filling out related incident reports and treating injuries that may have occurred.

Switching over to this comfort-first approach does not cost much money, but it is a significant investment in time and effort, Wyatt said. Still, the rewards are great—something driven home for Wyatt in a comment from one resident’s wife:

“She said, ‘If something happens to me, I know he would be all right.’”

Written by Tim Mullaney

Companies featured in this article:

AHCA, Beatitudes, CaringKind, Cobble Hill Health Center, ComfortMatters, Isabella Geriatric Center, The New Jewish Home